Case study: Raspberry Pi Foundation

How Raspberry Pi used continuous research helped guide the launch of CodeClub World.

“Before the pandemic hit, we had over 10,000 clubs running in 160 countries, reaching more than 150,000 young people a week,” says Laura, setting out the situation that she and her team faced. “From April - Dec 2020 our amazing team supported some of our clubs to deliver activities online. But the approach just didn’t work for many of them.”

The Raspberry Pi Foundation is most famous for producing affordable hardware. But they also have a range of products designed to teach computing.

One of these, Code Club, is a global network of free coding clubs for children aged 9-13 to learn how to make games and websites using Scratch, HTML & CSS and Python. Usually, the clubs take place in schools, after school hours, with a teacher or a volunteer to support the kids through the resources and materials Raspberry Pi provides.

But in March 2020, as the UK went into lock-down, Code Club came to an abrupt stop. Suddenly they stopped having product-market fit. “The number of children we were able to reach massively dropped, almost overnight,” remembers Laura, “And we had no direct way to reach the young people to support them to continue their coding at home.”

Step 1: Foundational research

So where did they begin? “We thought that the best way to start working out what to do was by developing an understanding of what children and parents' experiences of the pandemic had been,” explains Laura.

They quickly recruited eight parents of children aged 9-13 via their existing networks so that they could do it quickly and cheaply. They spoke to them on Zoom and used a semi-structured interview format. Their questions were intentionally open and not leading, and they wanted to learn about their experiences of parenting and supporting their children’s learning during the pandemic.

“Starting with this foundational, open-ended research was really key. If we’d dived straight into solving the problem or creating a product, we may have approached things differently and without a real understanding of what was important to parents and children.”

Through the initial research they found that most parents want their children to be able to play and learn independently without their support. They want quality experiences with clear outcomes. “And we learnt - there are some definite market leaders at the moment with children in this age group - particularly Minecraft and Roblox,” adds Laura.

Most importantly they also learnt that children were taking to these types of games to replace their face-to-face social lives so communication and collaboration was super important. “It was surprising to me how comfortable parents were with online peer-to-peer interaction,” says Laura, reflecting on the biggest insight that was to inform their next steps.

Things you can apply:

Use your existing networks to find your target audience

Use Zoom to conduct interviews or focus groups with open, non-leading questions

Keep iterating on this to build up a deep understanding of your audience

Step 2: Design sprint

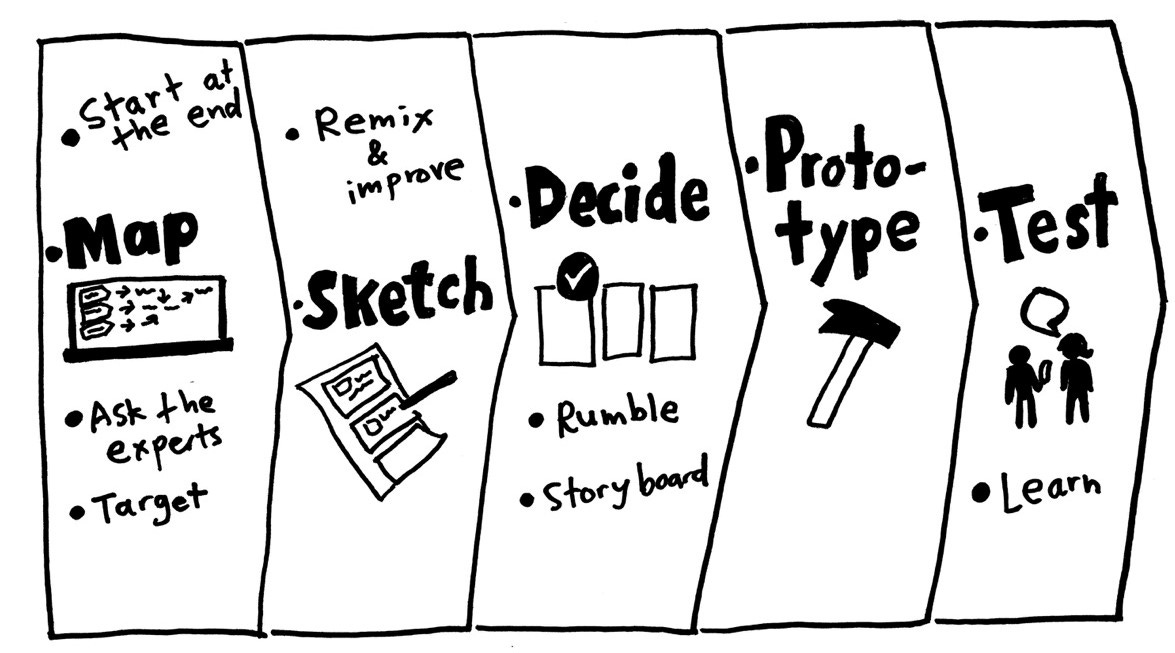

After this initial research, they spent a week running a Design Sprint, with a cross-functional team. They worked through this largely in the way that is recommended by Google Ventures.

“There were three particularly helpful parts of this week for me,” says Laura. “Firstly, constantly bringing our conversation back to the findings from our foundational research meant we stayed very centred on the user and their needs. Secondly, spending time using the products that kids are using everyday was very eye opening!”

But perhaps most importantly:

“Having the end goal of putting something, however lo-fi, in front of users on the final day was very motivating. I think this meant the group was focussed on synthesising our ideas and making something together. Never skip this part!”

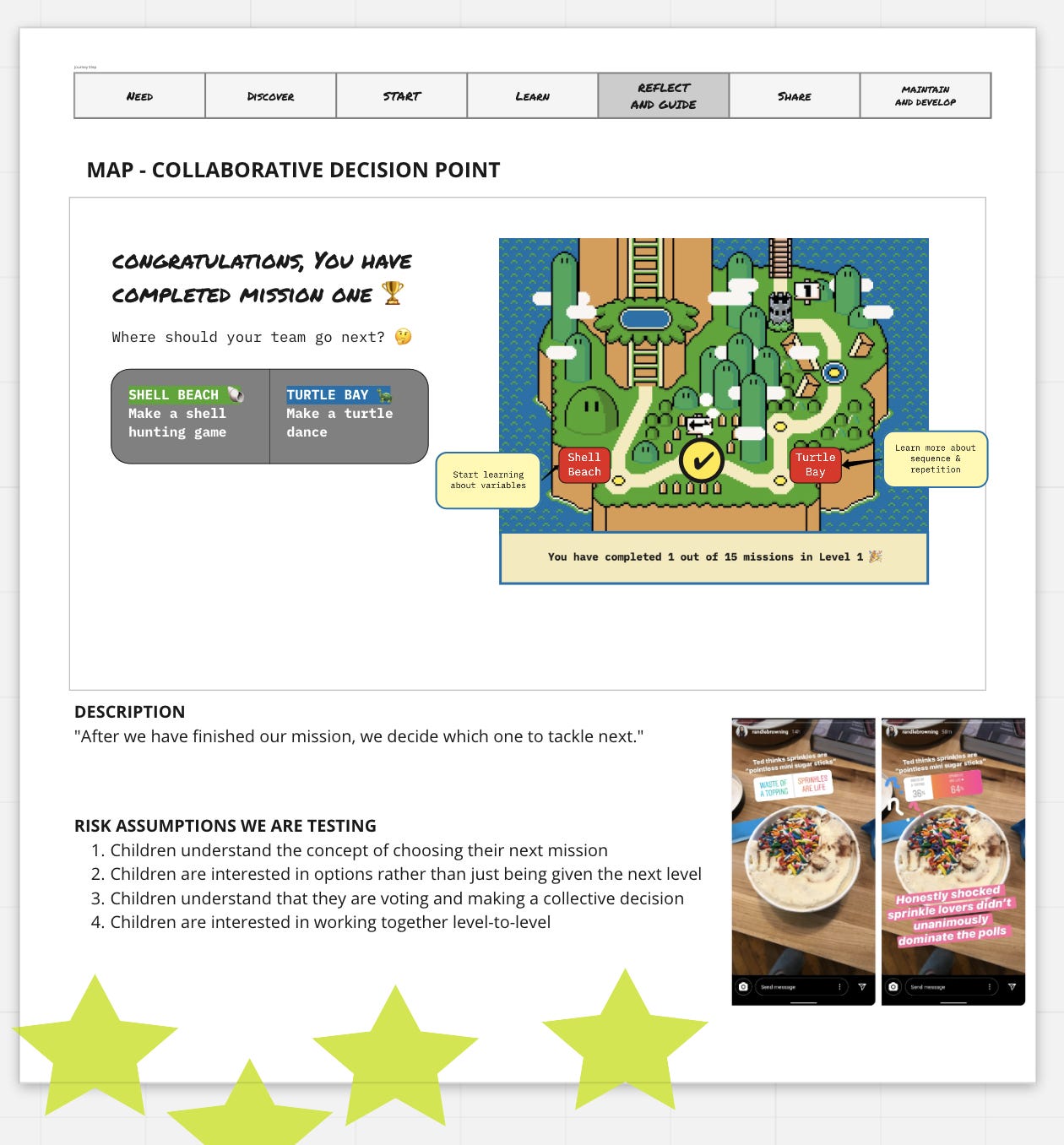

One of the outputs of the week.

Laura also recommends having a good facilitator, “you need someone to keep you on track and also challenge any groupthink or non user-centred discussion.”

From the testing on the last day of the design sprint, the team got a good idea of the sorts of things that were resonating with children and parents. But the ideas were still quite fragmented. “It was still so hard to imagine what the product we were creating would be or look like,” says Laura.

Things you can apply:

Run a design sprint, ideally with a facilitator to keep you on track

Use your findings from foundational research interviews to guide you

Make sure that you provide a hard deadline of testing something with real users to keep you motivated

Step 3: Creating a prototype

To her, it was very clear that next they needed to create a prototype that was more focussed on an end-to-end user experience. “I thought it would be a good forcing function for us to make decisions and give us an artefact to use in further research with young people.”

But before they did this, they really focussed on who their users were by creating simple personas. They decided that we were targeting children aged 9-13, learning at home without adult support.

They also decided on some principles to use as constraints. For example, making a mobile-friendly website that works on all devices rather than an app and also that the learning experience would utilise the best of Raspberry Pi Foundation’s constructivist pedagogy so children would learn to code through making stuff.

Laura, the Commercial Lead, the Director of Informal Learning and a Product Designer then worked over a week or two to create a prototype using Figma, the web-based, collaborative design tool. They took some of the best parts from the design sprint to create this.

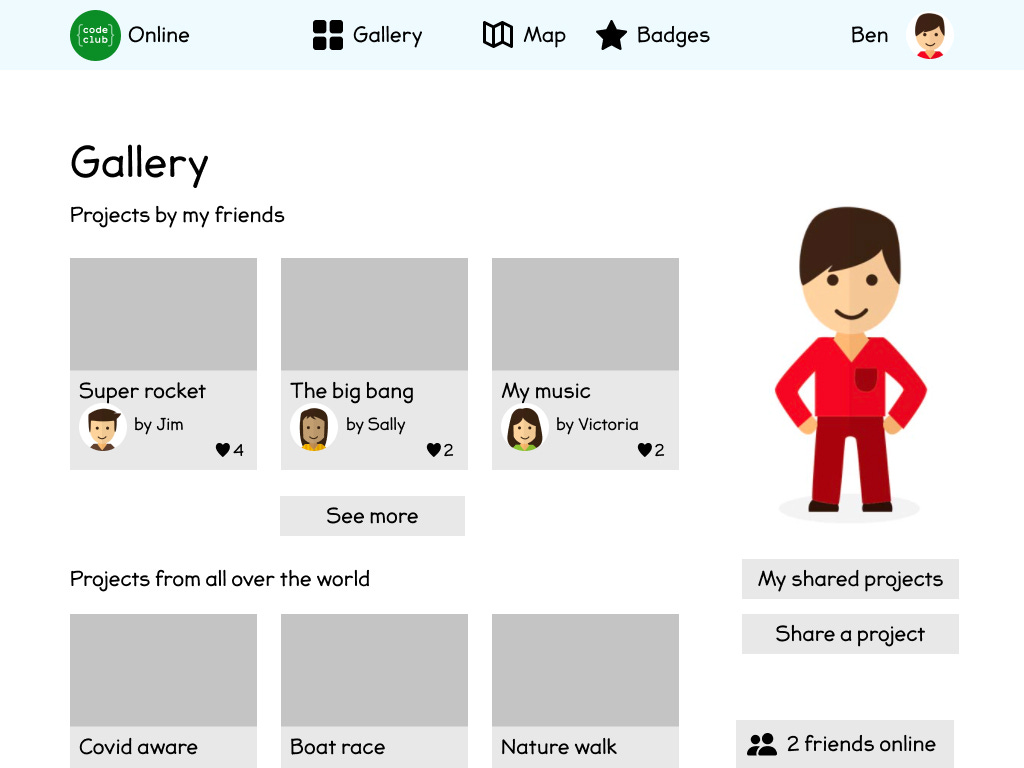

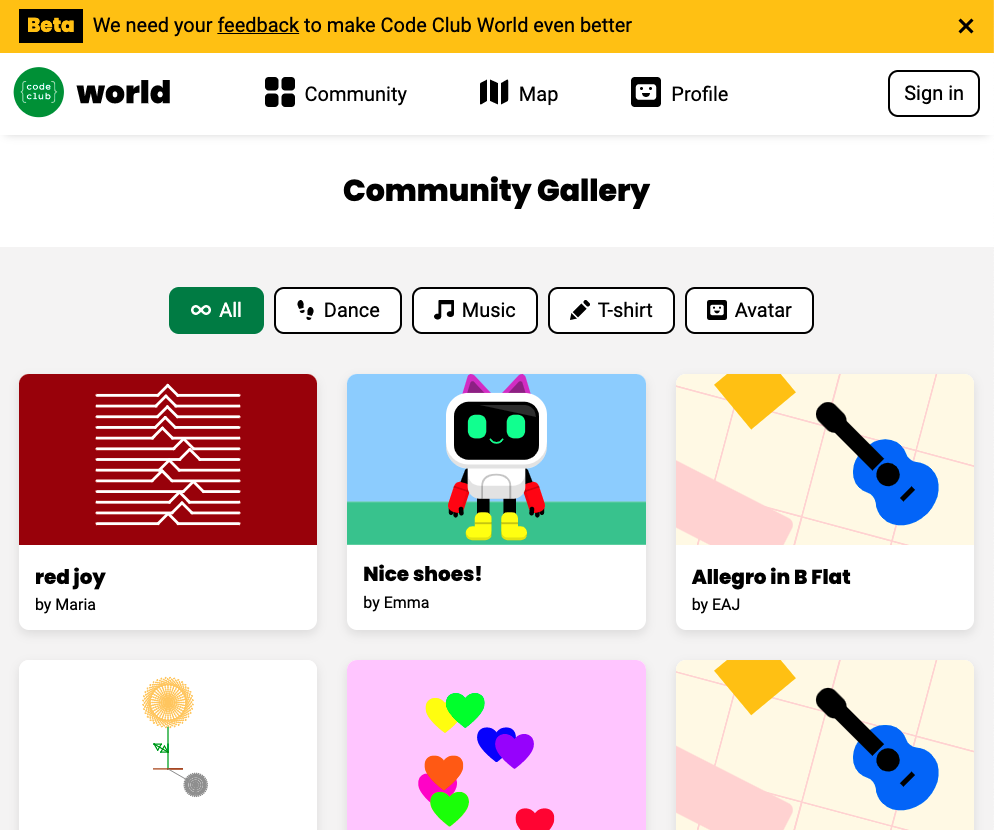

The gallery feature in the prototype.

“I believe it’s important to create a no-code prototype, because often building something with code is the most expensive and slow way to work things out,” explains Laura. “If you use paper or digital design tools you can find out much more quickly and cheaply what works and what doesn’t.”

After they’d made the prototype, they again tested it with their young audience. “At this point we were interested in the overall appeal of the concept, whether it resonated with them, and how it made them feel. We also used their reactions to assess which features were most critical for the minimum viable product.”

Things you can apply:

Use a tool like Figma to create rapid no code prototypes

Test them with your audience to understand desirability

Use their response to help prioritise key features

Step 4: Building a community of testers

Once the team had some confidence in the core feature set, they started to build something with code. But in order to make sure they had a lot of ongoing feedback they started to build a community of testers alongside this.

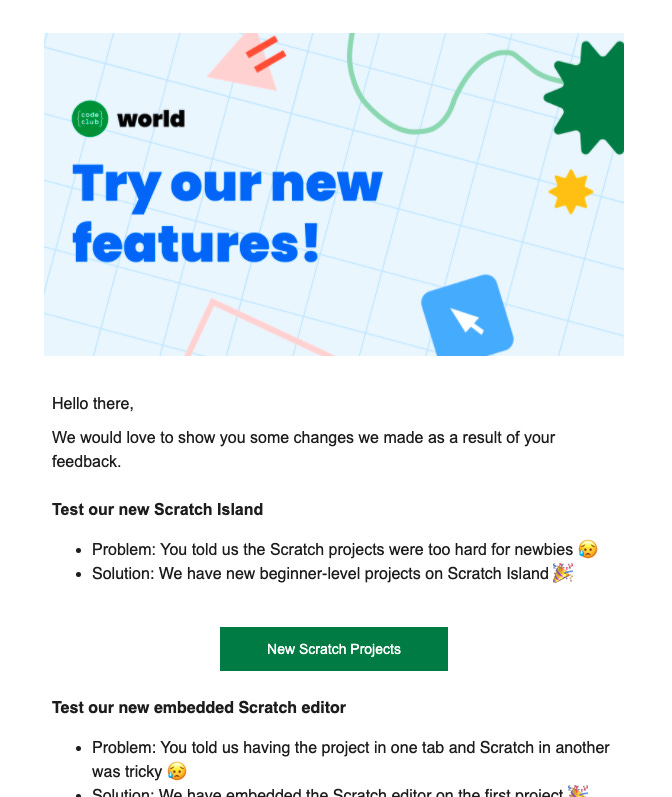

“To find these people, we promoted the fact that we were building something new and exciting in an existing newsletter and asked people to sign up as alpha testers,” explains Laura. “I would always recommend looking at your existing networks first to recruit, these people are likely to be very happy to help and enjoy the kudos they get from being an early adopter.”

They now have around 400 people on this list. They keep them updated on what we’ve built, encourage them to participate in surveys to help the team decide what to do next and ask them to volunteer for interviews.

“For the first couple of months, we aimed to have weekly user interviews with two different sets of children and parents. It was so amazing to be able to put anything we needed feedback on in front of them so quickly. We could show them in-progress design work or get them to test out a thing we had literally just built!”

The team varied their methods: from semi-structured interviews to desirability testing, and user testing. This fed directly back into the product roadmap: “The weekly feedback loop was invaluable and enabled us to make really quick decisions on things.”

The testers have been engaged from the alpha phase, which began in April to the beta product now, with the public launch happening in October.

Laura reflects that it’s not always been easy to keep them engaged during this whole process. “But the thing that seems to work is regularly updating our website and telling them what we’ve added and why we’ve added it. Often it’s a direct result of something they’ve said or done and so I think this is a really powerful way to engage them.”

Things you can apply:

Use your own users or an existing community to build an email list and recruit research participants

Speak to at least 2 of your users every week and get immediate feedback on your latest progress - vary your approach depending on what feedback you need

Keep the community engaged by showing what you’ve added and why and that it’s a direct result of their feedback

Product-market fit?

So has the process helped them achieve product-market fit?

“From a qualitative perspective I would say the signs are looking good,” says Laura. “The conversations I’ve had with young people and the looks on their faces when they have used the product have given me a lot of confidence in what we are making. And some of the feedback we have received has been really positive.”

Things are also looking good from a more quantitative perspective. To date, the Beta has had over 3000 visitors and their bounce rate, returning visitor rate, and other key metrics are aligned with what is considered “excellent” in comparison to their other websites. Plus, the session duration is high with a monthly average of almost 7 minutes with 20% of users spending 30 mins or more.

The gallery feature in the beta product.

And Laura is quick to point out that she thinks that this is because they are delivering on the original insights from the foundational research.

“We’ve made something that kids can do independently without adult support. We’ve created a high quality experience, based on clear learning outcomes and the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s constructivist pedagogy. We’ve borrowed ideas from video games to make it a fun and engaging experience. And we have the beginnings of a social experience,” says Laura, excitedly adding they have much more planned in this area.

Key takeaways

Laura’s story brings to life some of the fundamental points around product discovery and how this can be applied to the world of learning and edtech.

In order to design the right product, you need to:

Speak to your potential and current users regularly. Laura spoke to at least two sets of kids/parents every week. It’s something that you need to build into your process

Don’t just rely on user testing your product. Foundational research to find opportunities and desirability testing of products are also important

Be prepared to change course based on what you learn. Be open-minded and avoid leading questions in foundational research and have clear hypotheses to test in directional research

Finally, one of the best things about this story is how Raspberry Pi built a community to make it really easy for them to test. Which also gave them the opportunity to turn them into their first customers.