Case study: Makers’ trend riding

How Makers Academy navigated the head and tail winds of bootcamps, apprenticeships, the pandemic and now generative AI to train over 5,000 software engineers and build an enviable list of partners.

“We had multiple moments when we thought that the company was dead in the first year, because filling those cohorts in the beginning was really difficult. The numbers just didn’t add up,” says Evgeny Shadchnev, co-founder of Makers thinking back to their first months in 2013.

“The first cohort in February was nine people, the second was four, the third one was six... It was August when we got our first cohort that crossed 20 people. That felt absolutely massive.”

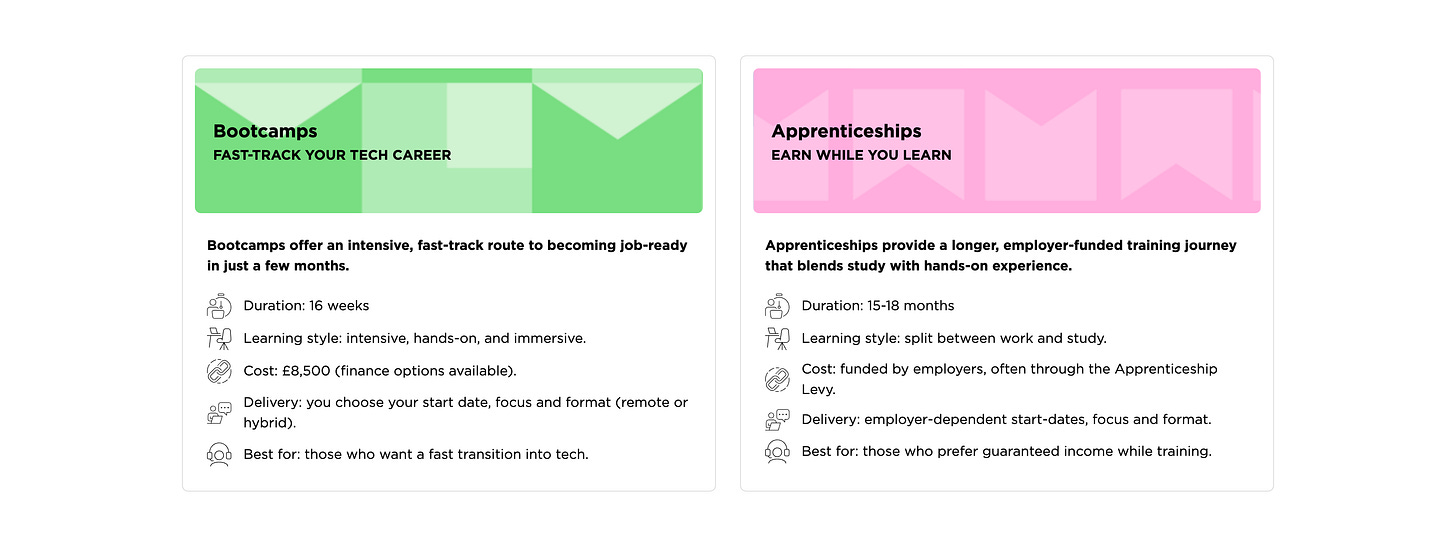

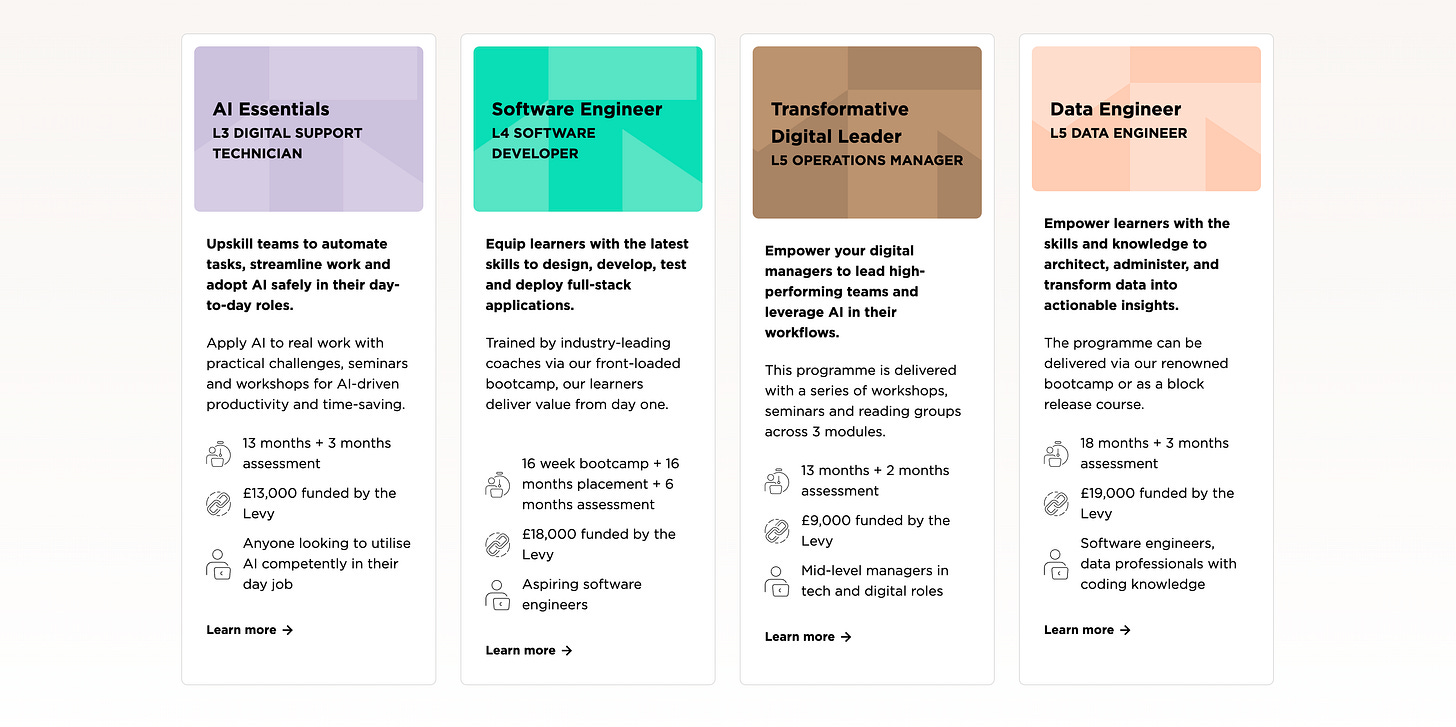

Makers, who started out in 2013 as Makers Academy, have now trained over 5,000 software engineers. Today they offer apprenticeships and bootcamps in Software Development, DevOps, Cloud and Data Analysis, plus AI upskilling programmes that go beyond training technology teams.

After quickly realising the importance of working closely with employers, they have established deep relationships with over 300 brands including Deloitte, HM Government, Compare the Market, Kraken, Google, Ford, Tesco and The Financial Times.

They are a B-Corp, and in the sector they are seen as one of the best at producing job ready graduates who, as well as being able to code, have great team and collaboration skills.

So how did they navigate the various headwinds and tailwinds to find and evolve their product-market fit? Their co-founder took the time to reflect on their journey.

The story is one of spotting and making the most of trends but also of grit, determination and taking an authentic, human approach to creating valuable outcomes - often in the face of existential threats.

Let’s jump in.

Spotting the opportunity

Makers began when Evgeny was working for the early stage VC Forward Labs in their startup incubator.

“We were trying lots of different things to see where there might be an interesting market opportunity. Makers was one of the ideas that seemed to show some early promise,” he remembers. His colleague Rob Johnson had begun exploring the idea and it immediately resonated with Evgeny.

“One of the reasons it was particularly interesting for me is that I studied Computer Science at university,” he recalls. “When I got my first job as a junior software developer, I noticed a big disconnect between the realities of the workplace and what my university experience had prepared me for.”

The pair sensed that there was a growing market demand for a different kind of software developer training. They created a landing page, put call-outs on social media and talked to anyone that would listen. “The tech community in London was smaller then, so a bit of Twitter, a bit of word-of-mouth and somehow nine people found us. That was enough for us to give it a go.”

The pair decide to go all in on the idea and find an office for their first cohort. “Once you commit to training people, they’ve quit their jobs and they expect you to be there on Monday, it’s not easy to just drop it,” he says.

They had their early indicators of product-market fit: people not only willing to pay for it but also willing to quit their job to do it. Now they had to deliver on the promise.

The first cohort and early ah-ha moments

Their guiding principle was that what they taught should be driven by the realities of the job market. They focused on the outcome: the goal of their students was to get a job as a junior software developer.

“A lot of the things that I had learned at university just didn’t make the cut because I felt it wouldn’t be directly relevant to their employment prospects,” says Evgeny. “Meanwhile, things like teamwork and version control and the modern tools that are used day-to-day, were not covered in Computer Science degrees at all.”

“So that’s where I started. I looked at my own experience as a software developer and tried to teach not what I learned at university, but instead what was useful to me every day in a working environment.”

Whilst this has remained the core principle of Makers programmes, their early approach to teaching developed rapidly. “One thing that wasn’t immediately obvious to me but became very clear over the first few months was that teaching people how to code basically doesn’t work,” he says.

“Standing in front of the whiteboards trying to explain how to be a software developer was a colossal waste of time,” he recalls. “What actually works is telling students to go and figure out how to do something. They start to understand the problem. They inevitably struggle. Then they come with their questions. You can give them a specific pointer and they advance a little bit. Then they keep struggling. But keep learning. They start powering their own growth.”

This insight became the second principle for the Makers approach: self-directed, hands-on, focusing on developing lifelong learning skills through projects, pair programming, and coaching.

The right trend and creating word-of-mouth

Whilst these early insights were helping them to develop an effective product, to continue to make progress they needed to find new students. They decided to run cohorts every four weeks to enable them to iterate fast and cover the fixed costs of their office and team.

“We were also optimistic that as well as teamwork within the cohort, teamwork across cohorts would matter,” says Evgeny. “The idea was not to start from scratch every single time, but to kickstart the learning process by having different generations of students learning from each other.”

These regular start dates also became an important growth driver. “Every four weeks, there was a group of students doing a public demo of projects they built and talking about the skills they had developed. We provided free pizza and beer and it was an opportunity to celebrate,” he says.

“But it was also an opportunity to invite potential customers. Students invited their friends and family. And so our graduations every four weeks became events we were looking forward to as an opportunity to celebrate, take a breath, before a new cohort began on Monday. But it was also the moment where we could attract new people as well.”

These events began to fuel the word-of-mouth that was so important to finding their next cohorts. Alongside this, their bet on the trend of people wanting to become software engineers and the emerging category of coding bootcamps started to pay off.

“We launched in February 2013. Literally four or five weeks later, General Assembly launched in London,” he says, remembering their mixed feelings about the established US competitor entering their market.

“This might sound like a problem on the face of it because it’s competition. But actually, it was really helpful. It raised awareness that coding bootcamps were a thing. If you saw a General Assembly advert and were interested, you would inevitably do your research, learn about Makers and quite possibly come to us instead.”

Being one of several new entrants in an emerging market tackling new unmet needs is often important to the success of a new venture.

Focusing on the community and finding ways to work with other new entrants also help them to build awareness and reputation.

“The world of learning how to code is very small. Everyone is connected to each other. There are plenty of small communities, people talk about each other and word-of-mouth is a very significant factor in the decision making process,” he reckons.

Finding opportunities for mutual value exchange with communities such as Codebar, Coding Black Females, Somalis in Tech, Next Tech Girls, and Muslamic Makers also helped them with another of their core goals: to inject a diverse stream of talent into the technology that in future would ensure a diversity of product and hiring decision making.

“We were keen to ensure that our student base was very diverse. Doing it in a direct way through quotas never felt right,” he says. “Instead, we reached out to underrepresented communities where we knew people were learning to code and offer discounts or invite them to host events at our offices.”

He says focusing on this early was important. “I’m happy that we did this from the very beginning because having now trained 5,000 graduates, if these were all white men, we would have made the industry even less diverse.”

These drivers of awareness and referrals propelled them into regular cohorts of 20+ students. But they realised that this still wouldn’t make the business sustainable.

Diversifying business model

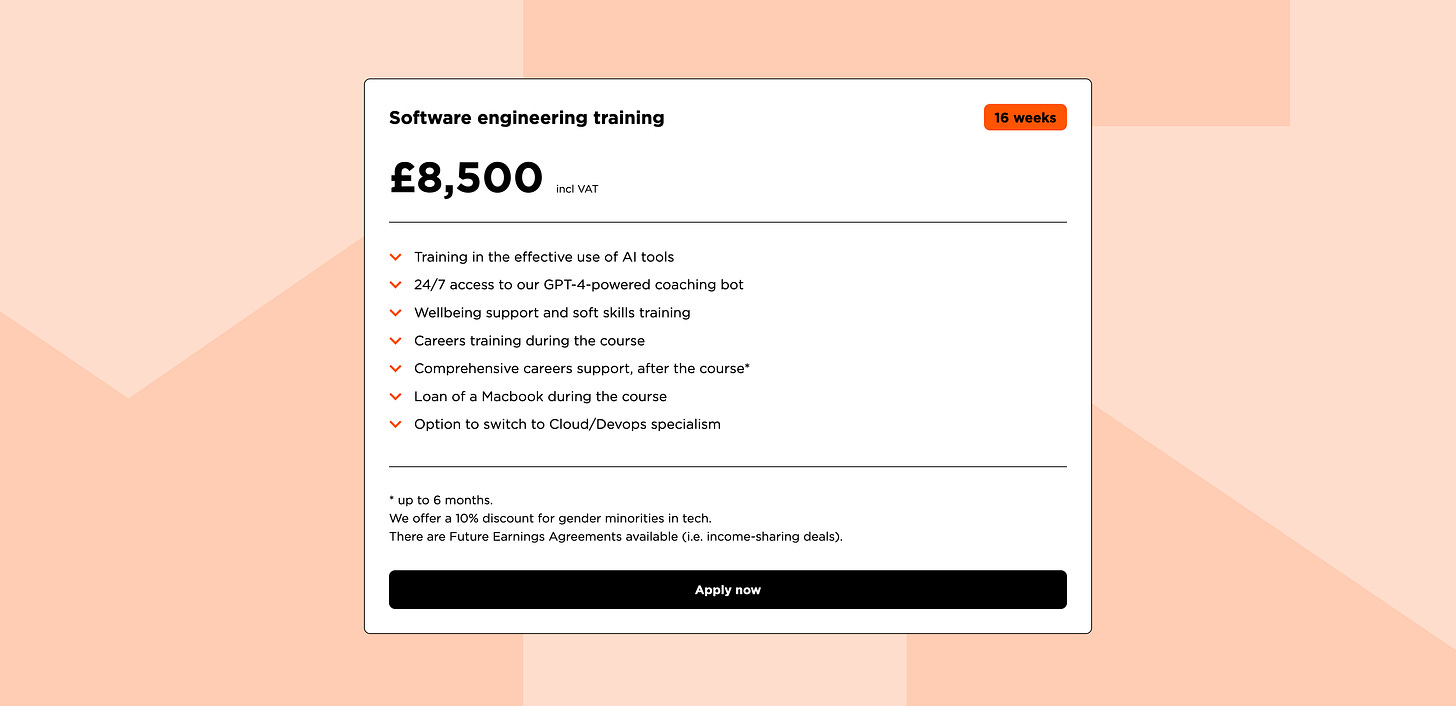

At the time, they were charging around £8,000 for their bootcamp. But this wasn’t covering their costs. In front of Excel, they started to face the hard realities.

“We knew that there is only so much an average student can pay. They are also paying their living costs and the opportunity cost of not working. So the actual bill is somewhere in the range of £15,000-£20,000, which is significant for an average consumer,” says Evgeny. “So there was no room for upselling them or trying to turn it from £8,000 to £25,000. We realised that unless we figure out how to make money from elsewhere, we are not going to stay in business.”

First, they experimented with a more scalable online model that offered the opportunity to reach a wider global market. “But we never quite figured out how to acquire customers on a meaningful scale globally because a huge part of our value proposition was helping people to get a job.”

“Doing that when you’ve got a cohort of students graduating together in London is difficult but doable. But if you’ve got one student in a village in France, one student in Venezuela, one student in South Africa, one student in Melbourne in a totally different time zone… how are you going to help them find a job?”

“We realised that our value proposition of helping people to get jobs only makes sense if students are concentrated in the same geography where jobs are.” This failure helped them to understand where they need to focus: employers.

“Every coding bootcamp that managed to stay alive over the last decade has figured out that it’s about selling to enterprises. And the companies that didn’t figure out how to make that move went out of business,” he reflects.

Initially, they found charging recruitment fees hard: “Anyone could come to our graduation ceremony and talk to our graduates. So why pay us?”

So they started to offer a premium access service. “If you pay us to hire our students, we’ll do our best to understand your requirements. We know our students really well and we’ll make a really good match before anyone else finds them.” Building these relationships enabled them to spot another opportunity: hiring their own graduates and placing them on a contract basis.

Creating these deeper relationships with employers and owning the whole pipeline also enabled them to improve their overall offer.

“If a student didn’t pass an interview, then it would be an opportunity to have a conversation. Okay, what did they miss? Is there anything we could have done differently?” says Evgeny, explaining how this feedback loop helped them adapt their teaching.

He says that this is a huge advantage of being in a small company where everyone was able to fit into a single meeting room. “The people doing admissions, people doing coaching, people doing career support. Everyone was in the loop. Should we not have admitted the student? Should we have trained them differently? Should we update our curriculum?”

This he believes is one of the big advantages over traditional education where the focus is on certification and the graduates navigate the world of work themselves.

“It’s a huge missed opportunity because if you can’t see the entire process from admissions to actually doing the job, then you’re missing opportunities to improve and deliver the outcomes students want.”

It also gave them a commercial advantage because of how aligned they are with employers. “Qualified talent is one thing. But a reliable stream of very diverse, high quality talent who are ready to do the job is quite another.”

This developing model, with recruitment as a key feature of their value proposition, led them to consider another emerging opportunity: the newly introduced apprenticeship levy.

Apprenticeships

The Apprenticeship Levy was introduced in April 2017 by the UK government. It is a tax on employers with an annual pay bill over £3 million, requiring them to pay 0.5% of their payroll to fund apprenticeship training. At the time of its introduction there were very few providers of software development training.

“At first I was not particularly excited by the idea,” Evgeny admits. “It felt like a lot of bureaucracy, compliance and red tape. And I wasn’t quite sure what exactly the upside was.”

However, they had recently hired someone with a background in entrepreneurship and technology and education who was ideally placed to understand the different perspectives and the challenge of becoming a registered training provider.

“We were a chaotic startup without many internal processes and without much documentation and with just one Slack instance with a thousand messages a day on every single channel,” he says. “Becoming a registered training provider comes with a long list of regulatory expectations of how we should behave and what records we should maintain. It was not exciting in the slightest.”

They hired a compliance lead who did a wonderful job of organising their records and ensuring their financial models to accommodate the counterintuitive way apprenticeships are financed.

“We got it done because the market was pulling it out of us,” he says. “Apprenticeships are free to the student, which is a big deal. But also if this money is not spent by the companies, it also disappears and so they also have a strong incentive.”

Rapid interest in apprenticeships helped propel Makers to their next stage of growth and today they are a significant part of Makers overall business. Makers now offer a range of apprenticeships in AI, Software/Cloud/Quality Engineering, Data Essentials/Analysis/Engineering and Senior/Transformative Tech Leadership.

But just as apprenticeships were gaining momentum, a new crisis hit.

The job guarantee and near death

Makers were one of the early pioneers of the job guarantee. If you had taken their programme and didn’t get a job within six months, they would refund you the cost of the programme.

“It was a bold brand promise,” Evgeny says. “In practice, though, it wasn’t difficult because pretty much everyone got a job within six months. People who wanted to get the job got the job. And so the level of refunds we issued was next to nothing. And it worked really well as a way to reassure and convert potential students.”

But in March 2020, the world went into lockdown and everyone stopped hiring. Maker’s bold brand promise started to materialise in a very scary way.

“We quickly realised that the financial liability on our balance sheet to our students who didn’t have a job was basically going to kill the business in the very foreseeable future,” he says remembering the enormity of the situation. “We also made an assumption that we are not going to see any new business-to-business revenue at all for the next two quarters. The hole in the balance sheet just looked absolutely existential.”

He says that as a board they had a “very lively discussion”. They were essentially left with two terrible choices: “Do we honor the liability and die. Or do we default on our promise to students and take the heat and probably also die, but just in a different way?”

Instead, their answer was to find a middle way. The team made a superhuman effort to handhold every student and to help them find a job - whatever existed on the market.

“We made some refunds where we had to. We pleaded with some of our students to give it a go for another three months before taking a refund. We did absolutely everything we could,” he says. “And somehow, by a bit of magic, a lot of hard work, and a small miracle, we made it through without defaulting on our promise. I still don’t fully understand how, because the scale of the challenge was absolutely sickening.”

I ask him if, knowing what he knows now, if he would still have offered the job guarantee? “Yes,” he says but adds: “With a caveat that sometimes there are circumstances outside of our control.”

Realising when the next phase needs someone new

This near death moment came halfway through Evgeny’s transition from CEO to Board Member. Why at this point in Maker’s journey had he decided the time was right to hand over to someone new?

He says that there were two fundamental reasons: one personal, one professional. “On the personal side, I was no longer enjoying my job on most days. I didn’t feel like I was in the right place. It was just a lot of stress. I don’t mind stress, but after seven years you start wondering if it’s going to be another seven years of the same,” he says with refreshing honesty.

“And from a professional perspective, the company needed a chief executive with a different kind of skills. I started the business as a business to consumer company to help students change their jobs and learn to code. By 2019, we were very much an enterprise services provider,” he explains.

“The new challenge for the CEO was to be inside the offices of Tesco and Deloitte and other large companies talking about their enterprise teams and helping our sales team to navigate the complex world of business-to-business sales. That was not my skillset. And perhaps more importantly, it was not the skills that I wanted to learn.”

He says that when he considered what the company needed for the next five to ten years, it was fairly clear that it would need a different set of skills. This helped him come to the realisation that someone else should be running the business.

A 14-month transition began that led to him stepping down in Aug 2020 and Claudia Harris taking over. “It was absolutely the right decision,” he says. “She’s doing a great job because she’s got skills that I don’t have.”

Evgeny now coaches founders going through similar transitions.

Another trend and existential challenge

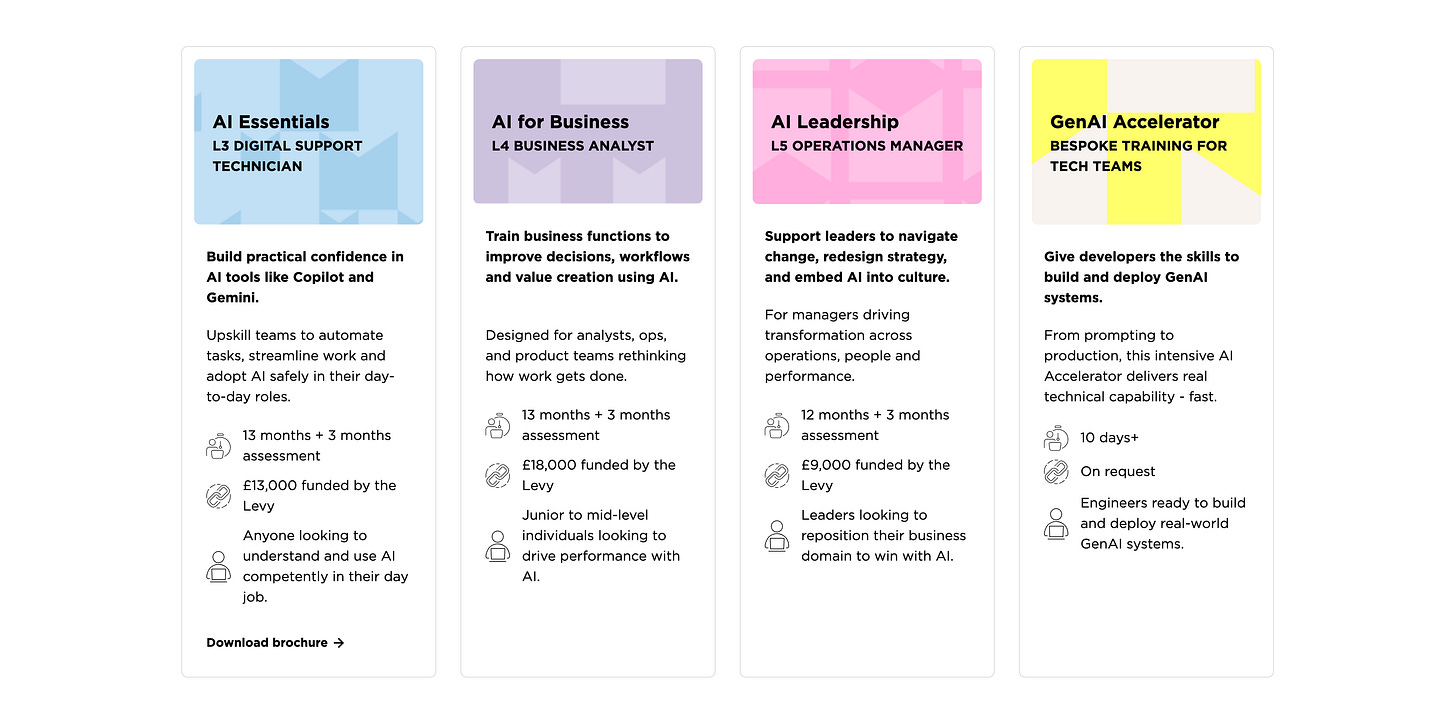

Makers are now leaning into the next transformational trend and potential existential trend: generative AI.

“AI feels bigger than the pandemic in 2020. That was a severe hit, but it was temporary in nature,” he reflects. “Today, with gen AI, I don’t think we’re going to return to any kind of normality we’ve seen in the past anytime soon. This transformation feels significantly deeper and much more structural.”

He says that not leaning into the transformation would be like ignoring the internet in 1997 and that this technology has the potential to be even more impactful. And it’s something that is disrupting the world of junior software engineers perhaps earlier than other industries.

“I’ve spent quite a bit of time this year leaning into AI assisted development. It’s incredibly powerful. AI isn’t going to mean that people are not going to be involved in writing code. But how software is being delivered is changing really rapidly. And the junior end of the market is suffering in the most obvious way,” he says.

“I don’t think that junior software developers are going to disappear in principle… But a lot of the tasks currently done by juniors are now covered much more cheaply by AI tools and often much better.”

He believes that we’re seeing a dramatic increase in the amount of software created. But there will be some people who are fulltime and “very serious about software development” but the vast majority who will be effectively building software by talking to our computers and using plain English everyday.

Meanwhile, Makers are successfully embracing this changing dynamic. Big companies take time to change and are still hiring lots of their apprentices. But they are also looking for support to transform.

Makers are helping them do this, with AI training and upskilling programmes and a suite of new AI apprenticeships that are designed for both technology teams and the wider organisation. “Makers is very much adapting to the times and trying to lean into AI disruption as much as possible,” he says.

I ask him what skills he believes are the most important for new talent to be learning. “Agency, self determination, creativity, ability to tolerate uncertainty. All these things are going to be very relevant, not just to entrepreneurs, but to pretty much everyone on the job market,” he says. “I also suspect that we are already at the point where being an entrepreneur is safer than having a job.”

His recommendation is to collaborate with and use the technology rather than competing with it head on. “Stay open, stay curious, try new things. All of us are figuring it out as we go.”

Lesson learned

We wrap up by reflecting on the conversation and the things that might be useful to others building new things in learning.

“Pay attention to the fact that no plan survives contact with reality,” he says. “By all means, make plans. But the journey of building a startup is a journey of navigating uncertainty, of waking up seeing very unexpected things in your inbox and thinking, ‘I had no idea this could even be a thing…’”

Assume there will be an evolution of the business model: Makers started as a consumer business but made it work when they focused on serving the needs of employers, first through recruitment and then through apprenticeships.

Start with the outcome and work backwards: their focus on getting students a job and owning the end-to-end process all the way through to recruitment enabled them to make a more impactful product.

Design for word-of-mouth: their regular graduation events, which celebrated student outcomes to a wider audience became an important part of their growth model, as was their authentic approach to the wider community.

Spot and lean into trends early: Makers successfully harnessed growing demand for coding bootcamps, the apprenticeship levy and now, the urgent need for AI training to build a position that is hard to replicate.

Bold brand promises are powerful - and dangerous: If you offer guarantees, model the unlikely risks and define clear “act of God” clauses and conditions up front.

“You are inevitably going to go through several moments when you think that there is no way out because the situation looks hopeless,” he sums up, reflecting on the nature of building startups. “And then somehow you’ll still find a way out. It’s basically part of the process.”

If you would like to explore working with Evgeny as a coach, please get in touch with him at evgeny@evgeny.coach and check out his Substack Unconditionally Human.

Makers are also advertising some great jobs: check them out here!